|

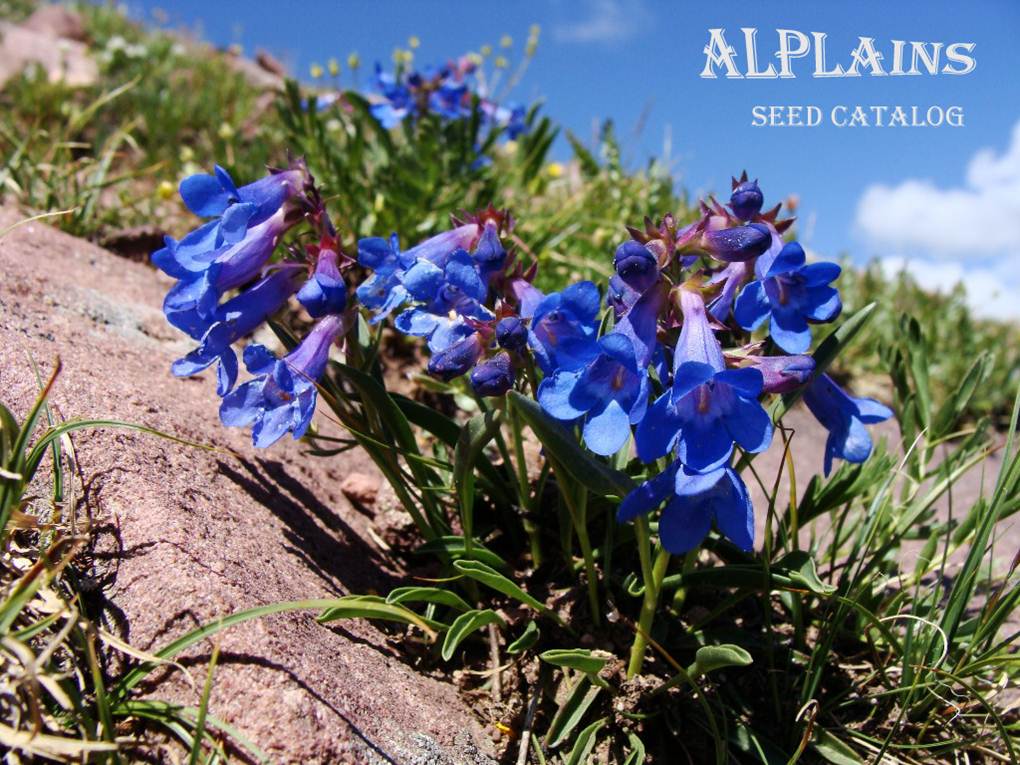

| Photo above shows Penstemon uintahensis in all its alpine glory at 11,500 feet on Leidy Peak in the Uintah Mountains, taken in August, 2008. |

Dear Growing Friends: Welcome to our 36th annual seed catalog! I decided I wanted to turn most of my greenhouse space into a rock garden so I spent much of April repairing or replacing panels and ripping out most of the benches. I scraped out most of the pea gravel so as to expose the bare soil underneath. Before bringing in any soil or rocks, the exposed concrete foundation and cinder block (32 inches high) had to be cleaned and coated with sealing asphalt, then covered with two layers of black plastic. I then could start hauling in limestone rocks that I had ordered from Texas long ago. The first course or foundational layer is the most important because it has to support all of the higher layers. Texas limestone is a great stone to use for building rock or crevice gardens since they tend to be flattish and have jagged edges. I also ordered 8 yards of amended topsoil to blend with some of my native topsoil as well as 100 bags of compost. Amendments included a slow-release fertilizer, mineral supplements, bone meal and blood meal. Much of the removed pea gravel was folded back in for drainage. All this work would take all summer to accomplish because in the meantime I had to take a few trips if I was to collect some seed. I took a break in mid-April to take advantage of the cool weather in the canyon lands. I headed out to the western slope in Colorado and hiked up Dominguez Canyon to see some petroglyphs. The main panel was right along the trail after 3.5 miles with smaller panels a bit further up. I was going to hike down the Honaker trail in southern Utah but I developed a bad cold and winter weather was threatening so I zoomed back home. Meanwhile, the greenhouse plants were all greening up, the Japanese maples were leafing out and the outdoor lilies were budding up. Alas, on May 24 a big hailstorm hit the Denver area and wiped out all my lilies and shredded what few leaves were already present on the local trees and bushes. I’m glad I hadn’t planted all the geraniums out yet. The lilies recovered somewhat but the resulting blossom show was rather pathetic. I was invited to sell seed at the annual NARGS convention held at the Botanic Gardens in Cheyenne, Wyoming this year. So I spent much of May preparing about a thousand seed packets which would be offered at their gift shop during the 4-day conference June 12-15. The wonderful staff there gave me a tour of the Gardens which was much larger than when I was last there 30 years ago. I was unable to attend the conference itself since I had already made plans for a seed collecting trip. The first day of the trip in early June, I spent some time around the Canyon City area where conditions looked pretty good. The Melampodium leucanthum plants were blooming and I discovered a population of Philadelphus microphyllus which I had looked for last year but couldn’t find probably due to the fact they were out of bloom already. Later, having gone over Wolf Creek Pass, I found a large patch of Iris missouriensis sporting many individual blooms in white surrounded by the usual blue flowers. Around Pagosa Springs, checking the local Townsendia glabella plants, they seemed a bit stressed and not as effulgent as usual. The next day, west of Cortez, Hymenoxys acaulis v. ivesiana was just coming into seed but I could see most of the local vegetation was even more stressed due to limited spring moisture. Heading down to Flagstaff, conditions only got drier and I could find no Calochortus flexuosus, Penstemon utahensis, Echinocactus, Amsonia or Mertensia macdougalii seeds. Only Baileya multiradiata managed a few blossoms along the highway near Cameron, Arizona. There were also a few seeds on the Agave parryi stalks left from last year south of Flagstaff. The next day I headed into the Mojave Desert and found only desolation. Some wild Asclepias subulata plants were trying to eke out a few blossoms but looked parched. Going over Walker Pass in southern California, however, I was pleasantly surprised to see that some of the Yucca brevifolia (Joshua tree) plants had bloomed and were in seed already. This was heartening news; maybe I would be able to find some seed in California after all. Indeed, driving into the western Sierra Nevada foothills yielded some good collections, including the rare Delphinium hansenii ssp. ewanianum, Calochortus albus and Triteleia montana. Driving through the Napa region the next day, I was delighted to find the local populations of Erythronium helenae had set a good amount of seed along with Calochortus tolmiei. Driving farther north along familiar routes yielded good amounts of Fritillaria pluriflora, Calochortus amabilis, Calochortus coeruleus, Allium hoffmanii and Erythronium citrinum v. roderickii. There were many disappointments too: the local Silene hookeri ssp. bolanderi and Balsamorhiza hookeri v. lanata populations were completely dried up. Southern Oregon is rich in flora and I managed to recollect many old favorites: Erythronium citrinum, Allium falcifolium, Lewisia oppositifolia, Phlox speciosa, Dodecatheon hendersonii, Pedicularis densiflora, Erythronium hendersonii and a new one—Arabis aculeolata. Up in southern Washington, I was hoping to find some Lomatium columbianum seeds and my preferred site north of Lyle yielded quite a bit. Northwest of Wenatchee, I was shocked to find the local Lewisia tweedyi populations had barely bloomed and set almost no seed. Driving home through Idaho and Wyoming I did not see any encouraging signs that this was going to be an abundant year. Thus endeth the 2025 collecting season. As noted last year, my seed inventory has become considerably depleted over the past few years due to my inability to collect enough quantity and variety to maintain that inventory because of the pervasive drought throughout the western states. I have made considerable strides towards building that inventory back up with more travel and collections over the past two years but I still have a long ways to go, especially in the flora from the Pacific Northwest and California. I plan to re-evaluate year by year whether to continue with the seed business or not. I enjoy the exercise and travel opportunities this business provides, not to mention all of the friends I have made over the years talking about varied botanical subjects from seed germination to ecology of wild flora. Eight seasons ago, I decided to discontinue publication of the printed catalog. I did issue a letter to all customers the year before and I think by now all of my customers have gotten the message. I’m grateful many customers have continued to follow me on the website alone and continue supporting me in my endeavors. -- Alan D. Bradshaw, Proprietor And in the interest of self-promotion, I would like to mention, mostly for the benefit of new customers, the following: In late 2011, I had the great honor to receive the Marcel Le Piniec award from the North American Rock Garden Society for "enriching and extending the range of plant material available to American rock gardeners." It has been a privilege to collect seed and introduce to the horticultural public many new species of plants. My customers are the cognoscenti of the horticultural world and are a wonderful group of people who have shown me nothing but kindness and encouragement in my endeavors. Thank you sincerely for all of your patronage and support over the years! We also continue to offer seed from the extensive cactus and Yucca collections of Jeff Thompson, an expert in this area for over 30 years. Now numbering nearly 200 different kinds, they can be identified by the "JRT" (field) and "TC" (cultured) numbers in the listings. We also thank Donnie Barnett for a selection of Opuntia seeds, indicated by "DB". -- Alan D. Bradshaw, Proprietor |

|

NOTE:

The twelve main seed catalog pages list ALL collections that are available for sale. In the interest of saving myself considerable computer time, I am no longer maintaining the "New Items" pages and I apologize if this causes anyone some inconvenience. Items listed on the "Archives" pages are NOT AVAILABLE but are listed there for your reference. When a collection sells out, it will be moved to the "Archives" pages. The 2015 catalog was the last printed catalog issued by us. For the 2016 season, there was a mailing with a cover letter announcing the end of printed catalogs along with a synopsis of my travels and a list of new collections made in 2015. After this, there are no more general mailings. All collections will be maintained on the website only from now on. For your reference, previous printed catalogs are available for $3.00 each. Issues available are: 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015.

Our Photo Gallery continues to grow. We will be uploading many more photos in the weeks and months to come. Stay tuned and watch our website grow!

|

To Contact Us:

Fax: 303-621-2864 E-mail: alandean7@msn.com

This entire website is protected under copyright law and no part may be reproduced by any means without written permission of ALPLAINS.

Last Update: November 16, 2025 |